Finn was free, though not in the “free to good home” sense. As a puppy, he was deliberately donated to become a search dog for a mountain rescue team. Finn logged several years of service and was called to go on many search and rescue missions, but everything began when he was just 6 weeks old and barely weaned.

Even at that tender age, Finn’s breeder (Pat Howarth of CownBred Collies in Lanchashire, Great Britain) knew he showed exceptional promise. Basically, he had a lot of career options: to become a winning show dog, a topnotch companion, or even a quality working dog.

Table of Contents

The Offer

Here’s how it happened, according to Pat:

“I was sat watching the local Northern News on tea time, and the Rossendale & Pendle Search and Rescue team leader was asking for volunteers to work with them – humans not canines. I watched the interview, because it was local to me and these guys are so brilliant.

Anyway, later that night while I was sorting my puppies out for bed, I looked at Finn and said, “We need a Smooth Search and Rescue dog, Finlay.” Then I let the adults out for the last toilet break and thought, That would be great for Smooth Collies – I’ll write a letter to the guy. So I did… not thinking anything would happen.”

The letter basically said:

“I’m 57 years old and very unfit, but I have a litter of Smooth Collies here. They are an ideal search and rescue breed and work all over the world, but none in their country of origin, Great Britain. If you want to consider a puppy, I’m more than happy to donate to one of your people.”

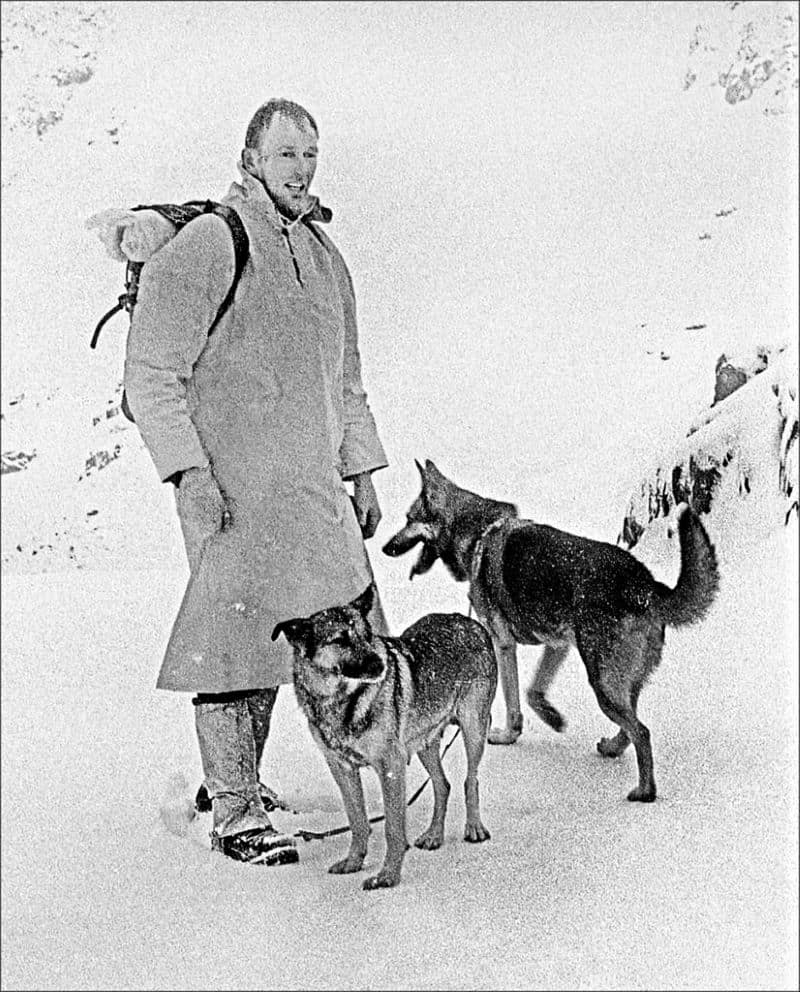

In a case of serendipity, Pat’s timing was just right for Stephen Garofalo (“Gruff” to his friends). Stephen had to retire his second search dog, a Border Collie named Roy, and was in need of a replacement partner. He said, “I’d heard of Smooth Collies but never thought of owning one until Pat offered me one. We did some research on the breed and decided that they have potential.”

The Chosen One

So Pat got a phone call telling her “what a lovely gesture” her offer of a puppy was, and two days later Stephen brought his family to meet the litter – all of whom were boy puppies. From what Stephen had said he looked for in a dog, Pat suspected Finlay would be his choice. He stood out from his brothers, being, in Pat’s words, “a big, very handsome, cool, laid-back dog.” If Pat had kept a Smooth Collie puppy, Finn would have been her pick of the litter.

Stephen said he usually relies on his instincts when selecting a search dog. He explained that fearfulness is really the main thing to look for, and if a dog is not fearful, “You can usually shape them to what you need.” But on that November day of 2007, Pat helped them choose.

“Steve’s wife and two children were playing with the pups, and I was watching them. I could see that they were all migrating to Finn, but not saying anything to each other. So I said, “Okay, let’s see who likes which pup. Point at the one you like on three. 1… 2… 3….” All five of us pointed at Finn. Weird – but obvious he was always the one.”

Pat had just had the puppies’ eyes tested for inherited eye defects (best practice due to the prevalence of Collie Eye Anomaly), so when Stephen asked if they could take Finn home with them that day, she agreed. In her opinion, “The sooner the pup gets to know his new owner, the better.” Stephen is of a similar mindset.

“The training of a dog starts the minute you get it. If you start with a puppy – which I think is the wisest choice – then you are going to bring it up. Getting an older dog can sidestep a lot of issues, but you may have to sort out somebody else’s mistakes.”

The Rescuers

It takes a massive amount of work before a human and canine are ready to go rescue people, so I’ll give background on what it took for Stephen and Finn to enter the ranks of the elite ones who perform this life-saving service. Before the stories of their search and rescue missions can be fully appreciated, it helps to know how they prepared before they could be sent out as a dog/handler team. (If you aren’t interested in dog training or the making of S & R team, feel free to skip down toward the end for specific mission info.)

SARDA (Search and Rescue Dog Association)

Finlay had some big pawprints to fill, but he had a competent handler and mountaineer to instruct him. Stephen had first had to become a member of a mountain rescue team to be eligible to become a search dog handler. Then he had gone through years of volunteering and extensive training to reach the level of graded (full) handler with the charity known as SARDA, whose “principle purpose is to train mountain rescue team members and their dogs to be competent search units.”

No one, not even the higher ups, receive wages. Their work is entirely funded by supporters and charitable donations, and all money received goes strictly into training and supplies.

“All mountain rescue work in Britain is voluntary and unpaid.”

In a previous article on search dogs posted on the RPMRT website, Stephen wrote:

“The history of mountain rescue dogs in Britain really begins with Hamish MacInnes, the fox of Glencoe. Prior to that, dogs had been used during the wars to locate soldiers and civilians. In the Alps, dogs had been used to locate avalanche victims for centuries.

During an Alpine trip, Hamish MacInnes saw some dogs being trained and had the idea of introducing them to Scotland to rescue climbers who had been avalanched. It was soon realised that trained dogs could be used to locate any missing mountaineers, and the Search and Rescue Dog Association was born.”

MRT (Mountain Rescue Teams)

It should not be supposed that the rescuers’ status as volunteers make them less professional. In fact, they are often the true “firsts” of the first responders, working in tandem with police and ambulance units. They may even be called out to assist in situations where a helicopter cannot fly due to poor weather conditions.

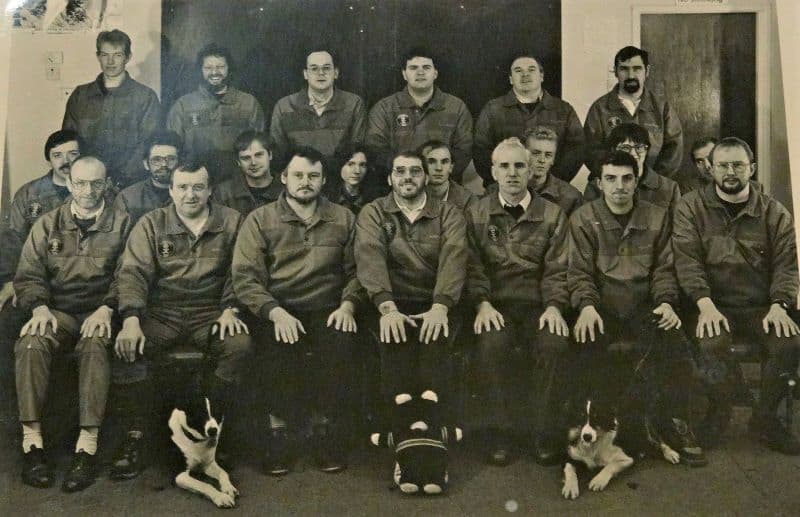

The Rossendale and Pendle Mountain Rescue Team (RPMRT) is an official, free emergency service providing a specialist team of trained volunteers 24 hours a day, year-round. Their website states, “We train every week and most weekends in our core skills of medical, rope rescue, navigation, communications, and stretcher work – along with water rescue.” It is clearly not for the faint of heart or the person with a passing interest, and it was this group that Stephen joined.

“The only thing that sets a MR (mountain rescue) team apart from a St. John’s ambulance unit is that our members should be competent enough to cope with an upland environment in virtually any conditions. An experienced team member is able to cope with steep ground, winter conditions, night navigation, and the fact that you may have to look after someone else besides yourself.”

Many is the hiker, jogger, or photographer who has gone out into the hills and had a hard fall or taken a tumble down a ravine, leaving them with a broken bone or a head injury. The mountain rescuers are adept at looking after themselves while extracting victims from the situations they have found themselves in.

Sometimes people suffering from dementia or Alzheimer’s wander off and become lost, while others set out for a nature walk and simply lose their bearings. Less commonly, children go missing. When a missing person is reported, that is usually when the search dogs like Finn are brought in.

Stephen's Training

Stephen joined his first mountain rescue team in 1982, when he was just 19. Before he could train as a search dog handler, he had to become a “body” (or dogsbody) at the young age of 22. As he said, “The road to becoming a dog handler is a long one.”

The “Body”

A “body,” in search and rescue speak, is someone who hides out in the hills so the dogs can find them and hone their skills. Stephen referred to the bodies as “a very important arm of the association” who “perform an invaluable service and make a massive contribution to the training of search dogs.” Though many bodies are MR (mountain rescue) team members or prospective dog handlers, a person needn’t be either to act as a body.

“Some are friends/family of dog handlers, and others are there for the social side and the opportunity to take part in an activity which saves lives. Being a body requires the ability to survive in the British climate for several hours at a time without moving, and thus bodies tend to be bivouac kings and queens. Some take great delight in finding devious hiding places, while others just use bodying as an opportunity to sleep off last night’s beer.”

Stephen’s time bodying allowed him to observe how the graded handlers trained their dogs, contribute to their training himself, meet MR team members from across the country, and practice dealing with the dangers of a hostile environment. Having to follow instructions and “lie out on the British moors and mountains all year round in all weather” was a test of commitment for those considering joining SARDA.

“I can honestly tell you that unless the sun is shining directly on you, it is never warm in this country.”

The association requires prospective dog handlers to volunteer as a body for at least 6 months, but Stephen bodied for 2 1/2 years before he started training his first dog. To this day, he says, he never forgets to thank the dogsbodies.

The Trainee Handler

When it comes to trainee handlers, Stephen commented that “many are called but few are chosen.” When he started, up to two-thirds of potential dog handlers didn’t make the grade. Some found it was more time-consuming than they had anticipated, while others, Stephen noted, “did not have the ability to train a working dog to a set standard.”

“Anyone can make friends with any dog… but it takes a long time, mutual trust, mutual forbearance, and mutual appreciation to make a partnership. Not every dog is fit to be partner with a man; nor every man, I think, fit to be partner with a dog.” – Hudson Stuck, dogsledder and Episcopal Archdeacon of the Yukon

The techniques of dog training can be learned, and skill can be gained through experience. But in Stephen’s words, “There is also a deeper element in that some people just seem able to communicate their wishes to animals better than others. Much depends upon body language and attitude…”

Conversely, Stephen pointed out, “Many people out there could train a search dog, but they are not mountaineers.” To become a qualified search dog handler, a person has to be both dog-savvy and hill-savvy. After all, the handlers of SARDA are part of a specialized fraternity within the mountain rescue group.

“To be effective, you need to be a master of the environment.”

Emphasis is often placed on canine temperaments, but in regards to the handlers’ temperaments, Stephen said:

“The association attracts a high proportion of individualists, mavericks, and eccentrics. Training a dog requires an odd combination of stubborn determination and pragmatism. This is reflected in the resilient personalities of many of the dog handlers, who react to knockdowns by getting up and attacking from a different direction or a different way.”

Throughout Stephen’s training, the SARDA evaluators were also watching to see if he had the necessary character traits of self-honesty and integrity. He explained that “liars and people who constantly overestimate their skills will not give accurate information during a debriefing and will make poor ambassadors for their teams.”

Stephen's Dogs

Skye

In 1987, when Stephen was 24 years old, he started training his beginner dog, a female Border Collie named Skye, daughter of a great search dog called Roscoe. All that time “interning” and making connections paid off, because she was descended from a whole lineage of search dogs who had belonged to previous dog handlers.

In Stephen’s estimation, “Broadly speaking, the best dog to start with is a Border Collie bitch. They are highly trainable, mature quickly, and have long working lives.” Skye became a certified search dog (making Stephen an accredited dog handler) in 1990, fully seven years after he had originally become a full team member. She lived from 1987 to 2000.

Roy

“Of all the team’s dogs, Roy truly stood out as a character. He was like a dog out of a Jack London story – an intelligent rogue of a dog. I really miss him.”

Stephen’s second dog, Rob Roy, was Roscoe’s grandson and thus related to Skye. Roy stayed healthy and worked well into his old age, living from June 1995 until July 2008. In that year, Finn was picked to become his successor, and Roy had some small part in the early education of Finn.

“Dogs are marginally better than bitches: since, being stronger, they can accept a greater workload and, tending to have bigger heads, they are thought to have a better sense of smell. The downside is that they are more willful and easily distracted, and to get the best out of them you have to get them on your side.”

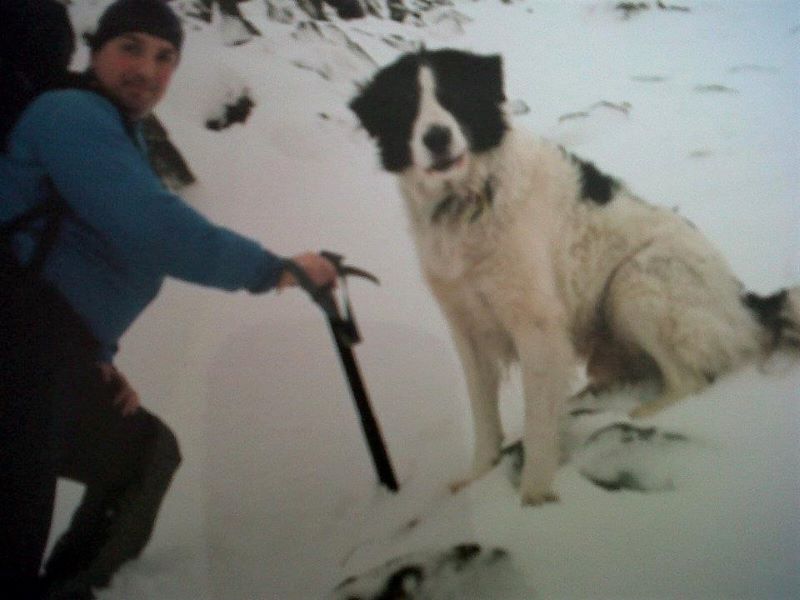

Finn

A Smooth Collie like Finn is not the typical choice for a search and rescue dog. Border Collies (the not-so-distant cousins of Smooth and Rough Collies) are by far the most popular breed to use, and are just more popular in general. Pat Howarth, who has been breeding Collies for nearly 60 years, said that on average, only about 70 Smooths are registered each year with the Kennel Club in the United Kingdom. (Maybe if Lassie had been a Smooth instead of a Rough Collie, things would be different.)

Arlene Harris’s daughter Lizzie volunteered on the rescue team with Stephen. When Arlene mentioned that she was considering getting a Smooth Collie, Lizzie said, “Oh, I think that’s what Steve has just got: I’ll ask him.” Arlene thought that would be too coincidental, since Smooths are now uncommon in Britain and she’d never even seen one in person. But Stephen brought Finn by to meet Arlene, and that’s how she ended up taking home Finn’s littermate Jack, and later also adopting the brothers’ grandmother, Tally.

Arlene said she had wanted a smart dog, one that could be off-leash trained without worry of it chasing livestock, and not as high-strung as Border Collies can sometimes be. She said:

“Dogs are so finely tuned – and I think Smooth collies are particularly sensitive to people’s emotions and to moods. [They are] a very loyal, trustworthy, intelligent breed capable of thinking rather than just acting on instinct. I can’t imagine having a better dog.”

Because Smooth Collies are a working breed, Finn did meet Stephen’s requirements to be “free-moving, hardy, and trainable.” Stephen emphasized how crucial it is for a dog to be tractable, since an overly stubborn dog could make extra work for the handler and possibly fail the final SARDA field test. (For example, cats may be more clever than dogs, but most of us have little to no success getting one to cooperate.)

“Trainability is something which has been selectively bred into dogs, and some have it more than others regardless of intelligence.”

Finn was also an appropriate size: a tiny dog would have trouble quickly covering large tracts of rugged terrain, while a giant dog would be difficult to maneuver into a helicopter. Other good-sized working (primarily hunting and herding) breeds that have made successful search dogs include German Shepherds, Hovawarts, German Shorthaired Pointers, German Wirehaired Pointers, Golden Retrievers, Labrador Retrievers, Siberian Huskies, Springer Spaniels, and various mixed breeds.

“Dogs have been bred to all shapes and sizes, but in the working breeds – which are most free from exaggeration – you can still see the lines of the running machines they come from. Many people have tried and failed with different breeds; but as it is generally the handler and not the dog which fails, it would be unfair to write off alternative breeds.”

Finn's Training

The first thing was to make a mountain dog out of Finn. This took time, as Stephen was mindful not to strain Finn’s developing joints in his first year of life. But Stephen regularly took him out on hikes, gradually increasing the distance of their mountain rambles and thus Finn’s endurance. Stephen explained, “Taking your dog onto the fells is as important as the rest of its training, so that it can acquire field skills, learn to recognise hazards, and build up its fitness at a steady and sensible rate.”

Stock Test: Wooly Mammals

Roaming the countryside also gave Finn a chance to get around some wooly livestock. “Much of Britain’s open land is farmland, and much of Britain’s upland is grazed by sheep,” Stephen explained. “Therefore, our dogs have to be safe to work around and through sheep.”

To progress through search dog training, Finn first had to pass a stock test to prove he was trustworthy around livestock. In search and rescue work, dogs are off-leash much of the time, often ranging far from their handler. They cannot be distracted and must not chase or otherwise harry grazing sheep. The farmers who allow rescue teams to train or search on their land are trusting them to ensure their animals come to no harm.

As you can imagine, not chasing sheep can go very much against the instincts of herding breeds like Border Collies and Smooth Collies. But that same innate desire can be a helpful thing when properly channeled. Stock training started young for all Stephen’s dogs, and it “largely consisted of redirecting the dogs’ chasing instinct away from animals, onto an inanimate object like a ball, and then from the ball onto people acting as casualties.”

In practice, the stock test is simple. Stephen said, “a flock of sheep will be encouraged to mill around your dog, and its behaviour will be monitored.” Finn passed, which meant he could then go on to the introductory assessment, a test of obedience.

Introductory Assessment: Obedience Test

Here is Stephen’s description of what Finn had to master to ace the obedience portion of his training:

“In the introductory assessment, you must demonstrate that the dog will bark on command, sit, lie down, come when called, stop and lie down on a recall, walk to heel on and off the lead, and do a stay for ten minutes with you out of sight for five minutes. All the above is useful to the dog throughout its life.

We rely on our dogs to bark as a means of indicating a find. Basic obedience is necessary for the dog’s safety, and the drop on recall can save you in a precarious situation where the dog is hurtling back to you. The stay is very useful when you are busy with other things and need the dog to lie still and out of the way.”

Stephen commented, “The standard is not very high.” Perhaps not, from the standpoint of an actual obedience competition; but as your average pet owner, I beg to differ. Precisely none of my three dogs would hold a stay with me out of sight, nor would they throw themselves to the ground mid-run! Which probably just goes to show the correctness of Stephen’s assertion that “Often, the hardest part of training a dog is training the handler.”

Stage One: Find Sequence</span<

Once Finn had the obedience basics down, he was ready to progress to stage one training. Knowing how to find people is obviously the most important thing a search and rescue dog can learn. When I asked Stephen about the sequence of events, he explained it like this:

“The dogs are taught to indicate a find by barking at the missing person’s location, then returning to the handler and barking at him. They then relay between the two locations, indicating the find as described, until the handler is with the missing person.”

Yes, the process does sound similar to the famous scene culminating in the much-repeated phrase, “What’s that, Lassie? Timmy is in the well?!” But it’s not that simple. Lassie, you see, had some background information to go on. But a dog encountering yet another human scent doesn’t know that stranger is metaphorically “in a well.”

“Human beings, let alone animals, struggle to perfect complex activities, and we usually know what the objective is. A dog has no way of knowing what its trainer wants until it has been shown, and it has to be shown a bit at a time – otherwise it will be confused.”

So Finn, as a prospective search dog, had to be taught to find people in stages, individually learning each step in a series of actions. Here’s how Stephen explained it:

“To train complex actions, dog trainers use a process known as “reverse chaining,” which teaches the last part first and then works backwards. The very last thing the dog gets is a reward, so it must be taught what the reward is and be very eager to get it before training can progress.

The dog should already be “ball pissed” – that is, mad keen to play retrieving games. We prefer toys to food because toys are more portable. The dog is taught that when it barks it gets a game, when it barks for a body it gets a game, when it finds a body and barks it gets a game, and so on until it has learned the find sequence.”

In this way, playful Finn learned that once he had successfully united Stephen and a body, he would be rewarded with a favored dog toy, and not by Stephen alone. “This all takes a considerable amount of input from the body, and ideally only a dog handler or a body who is good with dogs and enthusiastic should be used,” Stephen said.

“To begin with, there is nothing wrong with the dog knowing that there is someone out there. Letting it see the bodies going out and even having them call its name are legitimate practises. The handler should know exactly where the body is, or the bodies should have radios to tell the handler when the dog has been to them.”

Rather than track with his nose to the ground to find people, Finn had to be trained to use airborne scent. Stephen (and helpers) accomplished it this way:

“The body runs off in a “C” shaped line, ensuring that the dog crosses the scent cone as it runs out to the body. Very quickly, the dog learns this is the fastest way and becomes a dog that hunts with its head up rather than down. Upon crossing a cone of human scent, it must be automatic – what trainers call a “conditioned response” – that the dog will do its best to locate its source, indicate its find, and lead the handler to the missing person.”

To keep Finn from getting bored, his training was done “in short, sharp bursts, with a strong emphasis on play, and with regular changes of bodies and terrain.” But searches for missing people can be the equivalent of very long work shifts, sometimes over the course of days, so the next challenge was to get Finn to the point he could “maintain his performance for hours.” Once he demonstrated a mastery of the find sequence, Finn was ready for stage two training.

Stage Two: Fine Tuning

“As with all dog training, the trick at this stage is to make sure nothing goes wrong and to give the dog every chance of success.”

This phase of Finn’s training was really about smoothing out the wrinkles. Stephen said most people’s stay in stage two was very short. To level up, as it were, Finn had to cover larger areas and learn how to hunt using his instincts, with less prompting and input from the bodies and Stephen.

“Dogs are descended from wolves, which spend most of their waking hours on the move looking for prey. Mountaineering, like many hobbies, is a substitute for hunting. Most things that dogs are trained to do are corruptions of the dogs’ pack and predatory instincts. We merely channel what the dog does naturally.”

The strategy was not to head straight for a body’s location, but to the Smooth Collie a chance to smell the wind and follow the scent back to the hidden body himself. Stephen had to be patient and let Finn work his sniffing magic. The more successful finds Finn experienced, the more his confidence grew.

“Once the dog shows that it can work enthusiastically for over twenty minutes between finds and that it is not fazed by run-of-the-mill obstructions (streams, gullies, scree and small crags) it encounters whilst running down a scent to find a body, then it is ready for stage three.”

Stage Three: Crab Dancing

Since Finn had the find sequence down and the motivation to keep going, he entered his last “mini assessment” before the big, final test. Stephen and Finn couldn’t just show up at the final assessment and ask to be tested. Along with everyone else, they had to prove as a team that they were worthy to be invited.

Phase three is possibly more a challenge for the handler than the dog. Stephen said, “This stage often sorts out the mountain rescue people from the rescue people, because the areas get more rugged and the final months of consolidation take place in the winter season.”

Throughout stage three, the search areas became progressively larger, and Stephen had no foreknowledge of the bodies’ hiding place. Absent that advantage, he was truly hunting as much as Finn. But it wasn’t an aimless meander, as Stephen still guided the search. He said, “Working areas is theoretically easy: you have a box with some obstructions in it such as streams, crags, and gullies. So, all you have to do is take your air-scenting dog to the upwind end and start working.” In actuality, it becomes much more difficult.

“Search areas can be very confusing places. It’s surprising how much the ground changes once you are on it, and how obvious lines and boundaries evaporate or change shape once you are in proximity. Also, learning how to divide your attention between working the dog, keeping your footing, finding your way around, and maintaining a logical search pattern isn’t easy.”

The methodical way Stephen learned to maneuver his dogs through search areas, zigzagging “down from the top boundary in a series of large sweeps,” is given the fun term “crab walking.” It’s essentially the same way bird hunters like my dad teach gun dogs to quarter in the field.

As a team, Stephen and Finn “put on a good show in the closing months of the year” and received an invitation to attend the annual course. The invite was a vote of confidence, indicating they had been evaluated and thought likely to pass – though that was not a guarantee.

The Annual Course: Pass or Fail

The test takes place on the Cumbrian mountains, and the areas are chosen for their steep, chossy nature and their ease of observation from a valley bottom vantage point. For the handlers and dogs, it’s three days of clambering around on scree and blocks which are either iced or greasy – sometimes both. I have yet to know the assessment to stop for weather. It can be a stern test of all involved, including the assessors and bodies.

During the assessment the dogs are tested for reliability, worked over a series of large areas, and then marked on their performance. Features are scrutinised, such as the dog’s hunting abilities, its indication, its willingness to take the handler back to the body, and the team’s ability to cover the areas.

It wasn’t enough for Finn, Stephen, and the others being tested to find all the bodies hidden in their search areas. The dogs would be penalized if they did not inform their handlers of a found body or if they attacked sheep, and the teams could be heavily faulted, even failed, for performing with general inconsistency (less than 90% success rate) or not covering their areas thoroughly.

“Membership of the association is about trust… The final question is this: would you trust that team to search for a close relative tonight?”

In January of 2011, “after three days of winter weather, slipping and sliding, depression and exhilaration,” Stephen and Finn had cleared their areas, found their bodies, and passed the test. They “qualified to join one of the most exclusive dog clubs in the world” and were rewarded with “a plastic dog tag, a couple of dog jackets, and a waterproof coat – the total value of which did not cover a fraction of the cost of training.” Clearly, for the volunteers involved in this work, the rewards are not material.

The Missions

While each member of a MR team has a part to play, a search dog handler’s role within their team is highly specialized. Still, Stephen said handlers “don’t expect too much adulation” upon passing the final assessment.

“Training a search dog is done largely alone, away from your team. Most of them took no part in that eighteen-month to two-year labour of love and have no concept of what you have done. They were sat in front of the telly while you flogged up and down dark hillsides cursing the winter rain. What’s more, when you get to the other end of the journey and it’s time to dig that dog’s grave – they won’t be there either.”

“The dogs are invaluable to us, and they love being a part of the team.”

The Teamwork

Though not all the team members would fully realize everything Stephen and Finn had gone through to achieve the status of a qualified S & R handler/dog team, that didn’t mean Stephen lacked respect and appreciation for them. He pointed out that “dog handlers cannot act in isolation. We are only truly useful with the backup of a team to provide coordination, communication, sophisticated casualty care, and ultimately casualty evacuation.”

But Finn and his fellow search dogs became adept at working fairly independently. “Once an experienced dog is rolling, it hardly needs its handler,” Stephen said. “The weakest link in a dog team is the handler…” In fact, the canines consistently outperform their human counterparts.

“A dog is reckoned to be worth 10 men in daylight and possible a whole team in the dark. Statistics show dogs to be about 99% effective, and when a dog has been appropriately deployed, actual misses are virtually unknown.”

This is not surprising, given a dog’s natural equipment. Dogs may not see color the way we humans do, but their eyeset gives them a stereoscopic view of the world and their night vision is much better than ours. And they don’t have to lick a finger and hold it up to detect the wind direction. That’s what their whiskers are for. Plus, they have immensely superior senses of hearing and smell. According to the Calder Valley Search and Rescue Team, “It is not unusual for a dog to pick up a scent from a missing person 500 metres (547 yards) or more away.”

“A dog will work quite happily in conditions where a helicopter cannot fly, and their noses are much harder to fool than even the most modern technology. An air-scenting dog has the ability to cover vast areas of ground without actually going there. The wind does the work for it. It does not need an uncontaminated scent item, a start point, or a scent line to follow.”

“In an ideal world,” Stephen asserted, “dogs would be the first resource deployed on searches… in the hope of providing a fast conclusion. In reality, this seldom happens.” Issues arise with transportation, bureaucracy, and sometimes, as Stephen bluntly said, “deranged team leaders who want to make sure their boys get the glory.”

Usually, dog handlers work alone. “This takes a strong mindset… It also requires good hill skills, because you will often not be on familiar terrain,” Stephen said. Sometimes dog teams work in small groups. “In large spaces like fell sides and open moorland,” said Stephen, “we can form a sweep line. At other times, we work in pairs to clear opposite banks of a river or sides of a ridge.”

Many searches take place in urban outskirts, which means dealing with manmade obstacles as well as the rugged countryside. For such difficult areas, Stephen prefers to join and strengthen a search party. Though Stephen and Collie Finn were technically assigned to the RPMRT, they could expect to be called out to assist in searches with another MR team in any part of the country.

Stephen told me he has been on at least 400 missing people searches with his 3 dogs (that’s an average of 133 searches per dog)! But he said, “I’ve never kept count of the number of team callouts for injured people with a known location that I have been out to rescue.” The majority of their calls are for just such assistance, and they really are more rescue than search.

Stephen was understandably hesitant to discuss memorable missions he went on with Finn. As he said, “the missing people and their relatives may still be alive.” However, he directed me to some incident reports that are public access. While I can share some highlights of Stephen and Finn’s exploits, I must be necessarily vague on the details to protect others’ privacy.

To keep in top form, they also continued their training days with SARDA and MR teammates nearly every weekend – when not on an active callout. It should be noted that, regardless of who found what missing person, the team got the credit. They were truly, admirably searching for people in need, not hunting for personal praise.

When Dogs Fly

In preparation for being flown out to searches in remote, inaccessible locations, Stephen (Gruff) and Finn attended a helicopter training day with their teammates at RAF (Royal Air Force) Leconfield. This involved being winched up into a Sea King chopper by a 250-foot-long steel cable. According to the RPMRT report:

A special dog harness is used to hoist the dog into the cabin along with the handler. We didn’t notice at the time, but Finn may have had a bit of a twitch and released something from certain glands found close to his tail on poor Gruff. Once Gruff warmed up again back inside, we all knew about it.

Stephen commented about how the smell permeated his team kit, requiring a thorough washing. (If you’ve not lived through a dog releasing his anal glands near you, count yourself fortunate.) Apparently it was being lowered down that Finn disliked. I don’t blame him; I have no love of heights and wouldn’t appreciate being shoved out of a hovering helicopter either.

When Avalanches Strike

But Finn did improve with practice. A good thing, because Stephen and Finn would later be asked by the RAF to assist in a search for avalanche victims in Scotland. Finn and Stephen were already in the area, as they had been participating in a nearby SARDA avalanche training course; but to get to the site at the Chalamain Gap, they were airlifted by a helpful wildlife group that was researching pine martens in the Cairngorm Mountains.

Finn had the ability to scent a person buried beneath more than 6 feet of snow, and he had been trained to begin digging on command once he had indicated his find. Of the 12 people who had been on the slope when the snowslide struck, 3 did not survive. Stephen said, “We are always hoping to find victims who are alive and uninjured, but sadly it’s not always the case.”

“A dog is still the best tool for finding avalanche victims.”

When it comes to snow rescue, dogs are once again more suited to this frigid job than humans. As wolf descendants, many breeds are still double-coated, Smooth Collies included. Finn, though the shorthaired version of a Collie, had a thick layer of fur to keep him warm. He occasionally wore SARDA-issued weather jackets, but they could get easily hung up on brush and hamper his movements.

Structurally, dogs are also very cold-adapted, though the downside is this makes them much less heat-tolerant.

“Arteries and veins passing close to each other in the limbs act as heat exchangers, warming blood as it returns to the heart. In cold conditions, blood flow to extremities is retained, so they do not freeze as easily as ours do. The main muscle blocks operating the legs are close to the body, so they stay warm and work better in the cold.

Dogs are hardy, and they will survive in conditions which would kill many other domestic animals. I know of two search dogs, which had been lost in severe winter weather, who were found several days later – none the worse but for a little weight loss. Both dogs were lost in blizzards and ended up sleeping in the snow with no food.”

When People Are Lost

S & R work gets sensationalized, but often it is anything but. Sometimes, the team would be called out to help in another locality, search for several hours, clear their areas, and basically have to report to the authorities, “He’s not here; you’ll have to look elsewhere.” That may sound unhelpful, but it’s actually great for narrowing things down. (Rather like a room-by-room search for your missing car keys.) Here’s a sample report excerpt:

The RPMRT SARDA search dog Finn, handler Gruff, and Deputy Team Leader Graham (acting as a navigator), were called out by our colleagues in Bolton MRT for a misper search. The misper was not found and police enquiries are continuing.

Here’s another sample of a fairly typical callout log:

Our team were contacted by Greater Manchester Police requesting assistance with a search for a high risk missing person… After a brief conversation with the Police Search Manager, our team were deployed. SARDA England Air Scenting MR Dog Handler Steve Garafalo and his Search Dog Finn was in attendance. Bolton’s MR Trailing Search Dog handler Steve Nelson, with his Trailing Search Dog Boris, was also contacted to assist.

Several areas of interest were searched, however the missing person wasn’t found within these search areas. Greater Manchester Police contacted our team to state that the missing person had been found safe and well.

While some search results were inconclusive (at least at the time), others were tragic. One of Stephen’s social media posts simply said, “Another search concluding with one less man in the world.” But if they didn’t locate someone in time to save them, they were still providing closure for that person’s loved ones. In some cases, they would be asked to find someone even when there was little chance they would still be alive.

“The dogs are trained to find live people. The simple truth is that the longer someone has been dead the less chance there is of the dog finding them. Whilst we do occasionally get called out to search for people who may be deceased and have had many successes, our primary purpose is to save lives.”

The SARDA search dogs like Finn are by and large air-scenting dogs trained to follow windborne scent, though a few used in urban areas are trailing dogs. (Only a specifically trained cadaver dog is truly adept at locating dead bodies.) “The problem is that dogs live in a scent-orientated world,” Stephen explained. “Once someone dies, within a few days all the residual smell that the dog identifies as human is gone, and the body just becomes an object to the dog.” When a search dog finds a deceased person, they have usually not been missing for long.

“I also believe that dogs can have ‘Lassie moments’ where they recognise the situation and respond appropriately, but I would not depend upon a dog to do anything more than it has been trained to do.”

When a little girl went missing in Wales, it was a very high profile case and the eyes of all in Britain were watching. Eight Rossendale and Pendle team members, plus Finn, were dispatched to Machynlleth to aid in the search, which went on for several days without success. (Much later, her convicted killer went to prison for life.)

Of course, they had their share of more joyful conclusions. In one celebratory social media post, Stephen laconically commented: “Two searches this weekend and two live people recovered, which is nice.” And people are grateful. On the RPMRT’S Just Giving donation page, one touching comment reads:

“I am taking part in this for Rossendale and Pendle Mountain Rescue Team, because this amazing team saved Wilson’s life.”

At times, things got pretty exciting. Not in a “yay” sort of way, but in an intense and stressful sort of way. Here’s a condensed RPMRT callout incident report to prove it. (I left out the part about the punctured tire.)

Two men called 999 reporting they were lost on Pendle Hill. Team Leaders spoke to the pair on their mobile to try and establish where they were… Hill parties, including Finn our search dog, were dispatched to carry out path searches. There was a worry that one of the men had a possible head injury, so a rapid response was essential.

No sooner had the hill parties commenced their searches when a 2nd call was received by the Police for 4 males also lost on Pendle Hill. The group said they were uninjured but cold and wet, and that one was diabetic… After 30 minutes of searching, the group of 4 was located and escorted from the Hill, none the worse for their ordeal.

The Police helicopter attempted to reach Pendle Hill but was beaten back by the rain and cloud that had descended on the higher areas of moorland. The remaining 2 missing people had still not been found. We had 3 hill parties on foot searching and three 4×4 MR vehicles searching the area. After 2 hours of searching, the hill party found the 2 missing people…

Bodmin Moor is a granite moorland in Cornwall, an area where many rivers have their origins, and it was also the scene of a successful search in which Stephen and Finn took part. It was the farthest Stephen had been into the South West of Britain since 1973. As he said, “You get called all over the country because [the dogs] are so good at the job.”

Community Outreach

Sometimes local businesses like Downham Ice Cream Shop hold fundraisers to support the volunteers’ vital Search and Rescue work. At this particular event, Stephen, Finn, and other members of the RPMRT displayed their rescue equipment to the public, and many good-hearted citizens put money into their collection buckets.

Perhaps my favorite record of community outreach was this gem, particularly the bit about Finn’s participation.

Chairman Graham and SARDA team member Steve ‘Gruff’ Garofalo visited Bury Grammar School Boys. These boys had chosen RPMRT as their “house charity” and had raised some money to present to the team. Graham talked about the team before recalling a gripping tale of a past S & R, which had 200 boys on the edges of their seats. Finn made quite an impact too, making suitable doggy noises at appropriate times in the story.

It seems Finn may have made a habit of interjecting during human speeches, as per this announcement about a RPMRT training event: “Training tonight is on search dogs… It’s being given by our very own dog handler, Steve, and no doubt Finn will add his woof at the appropriate time.”

After 35 years with Rossendale and Pendle MRT, Stephen transferred to the Calder Valley Search and Rescue Team in 2018, so the last year or so of Finn’s working career was spent as a search dog for CVSRT.

One of Those Classic Ones

The trouble with dogs is that they don’t live forever, much as we wish them to, and the experience of losing one does nothing at all to soften the blow of losing another. Each of our dogs’ lifetimes spans but a decade or so of ours – not nearly enough time. On January 29, 2019, Stephen simply posted in his understated way, “Today has not been a good day. I have had to put Finn to sleep.”

For 11 years, Finn had slept in his bed on the floor next to Stephen’s. They had gone everywhere as a team. Finn had trekked up hill and down dale with Stephen and improved the lives of so many he came in contact with. Together, they had done what they truly loved to do and derived immense satisfaction from each other’s company. Finn had known how to work hard, take joy in it, share that joy with others, then come home and truly relax. That’s more than a lot of us humans ever learn to do.

“He was a happy, confident dog who really liked people.” – Stephen

How can you sum up the life of a dog, especially one as grand as Finn? And how can you offer meaningful sympathy to someone who is suddenly, unexpectedly bereft of their life’s companion? You can’t – not really. But you can try, as I’ve tried, and as many of those who knew Finn tried. The comments of sympathy that poured in made a eulogy for a great dog…

Nick: I’m sorry, mate. What a fantastic team you were; what a character he was. Take care and sleep well, Finn!

Tracey: I will always remember him using his avalanche training to find us under a tarpaulin. So close to being dunked that time as he was so strong and determined to find us under there, and we’d chosen to hide a bit close to the river. Fast lesson in choosing your hiding places carefully when bodying! Beautiful chap.

Chris: So sorry to hear that, mate. Some of my happiest times on the hill included Finn trying to “get through the snow” to me at toddy. Hope you’re as OK as you can be. Thoughts with you and Finn.

Kate: I’m sorry you’ve lost your friend. Finn was a lovely dog, so elegant and athletic.

Hannah: You’d revoke that comment if he’d pounced on you, right in the middle of your stomach! ♥️

Elizabeth (Lizzie): I’m so so sorry!!! 😔😢😢 I still remember the day you brought him to base and said, “Come look what I’ve got.” Arlene wouldn’t have Jack now without him. Much love and thinking of you. People who have dogs get the heartbreak of losing a best friend. Take care.

Kirsty: Oh no, I’m so sorry. He was such a lovely, amazing boy and such a faithful companion for you.

Christyne: Oh no, so so sorry to read that, Gruff 😥 He was such a lovely, big fella. It hits hard when you have such a close working relationship with them.

Sam: I was found by this beautiful, clever boy several times. Good boy, Finn, sleep well. 😥💔

Charlie: So, so sorry to hear your news. It’s every dog handler’s hardest decision ever. Take care.

Peter: So sorry to hear this, Steve – hope you’re coping. I will personally miss the most laid-back, chill dog. He could lay out havin’ a kip (nap), when less than 2 feet above him all hell was breaking loose. 🙂

Stephen: He gave you ALL he could and in return you gave him a wonderful life. Together you achieved things some people and dogs can only dream about.

Alex: We have both been there before – not a good time. BUT search dogs have had a great life, playing hide and seek BIG TIME, playing on the hills. I feel your pain.

Duncan: Steve, I’m so sad to hear this. He was a great lad who had the best of lives with you. Will be fondly remembered by all those who bodied, trained with, or had the good fortune to meet him.

Bryan: So sorry, Steve. I know how much you cared for your dog.

Rod: Sad news indeed. However, Finn will not be forgotten – a bonny lad and a brilliant search dog. RIP Finn.

Laura: I have a real soft spot for Finn, who was the first dog that I got to see working when I started bodying for CVSRT. He was a great character, and I’m glad to have had the chance to know him.

Andy: In the words of the Victorians, Finn was a “quality dog.” He served SARDA well and was a great RPMRT member! May he now run free, chase whatever he wants, and rest well. RPMRT are thinking of you and will see you on the hill, listening out! 😔🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻🙏🏻

Other terms people used to describe Finn were: cracking pooch, top dog, certainly a class dog, such an ambassador for the breed, fine team member, such a gentleman, brave and wonderful Collie, superb dog, not just a pet but a partner, lovely chap, and a prince among dogs.

Wayne O. shared this memory:

“Such a sad coincidence that this photo should come up on my memories today. Sadly, search dog Finn left us today. He and Stephen were a fantastic duo and Finn had one very distinctive bark. I can hear him now. Take care, Steve and Denise, and remember all the good times you shared. RIP Finn. Love from the Oggies.” 🐾🐾❤

Pat Howarth, as Finn’s breeder, is justly proud of what Stephen and him accomplished together.

“Steve lived and breathed Finn: they were always together. I’m so proud of them both, and Steve is now a good friend. He’s a lovely man and such a decent person. Steve is a brilliant owner/trainer and always got the best out of Finn. He brought him over to visit a good few times, and he was always so well behaved. Steve starts to “blub” whenever he talks about him, and says he was the best and he thinks of him every day. So do I, whenever I see his pictures.

Finn passed a year ago, and whenever I think of him I cry. But he did so much for Smooth Collies; he was awesome. Finn became a bit of a celebrity here and in other parts of the world. Everyone loved him. He was the best ambassador for this brilliant breed you could imagine, to show the world what a real Smooth Collie is….. was. He was beautiful and had the sweetest temperament you ever saw in a dog.”

In honor of Finn, Mountain Rescue Search Dogs England posted:

With great sadness, we report the loss of one of our superheroes. Search Dog Finn was 11 years young… Finn became ill, and following vet treatment and further tests, his liver scan showed a large, inoperable tumour. Finn was not himself, and Steve had to make the decision none of us ever want. Finn’s final day involved lovely walks with Steve and with body Denise. He will be sorely missed by Steve, Denise, and their family and will be a massive loss to us all here at Mountain Rescue Search Dogs England and to Calder Valley Team.

“I think it’s fair to say Steve and Finn were soulmates.” – Arlene, owner of Finn’s brother

As far as dog relatives, Finn is survived by his litter brother, Jack, and by his great-grandson, Rolf, who is now Stephen’s search dog in training. Arlene said, “Rolf looks a handsome pup. I’m sure Rolf will be spending many hours up in the mountains.”

Jack: A Search Dog of A Different Sort

Arlene, Jack’s owner, volunteers with a local conservation group to help preserve the Eurasian Badgers, and Jack assists her.

Jack is almost identical to Finn (except upright ears and less coat), but skinny. I do feed him; it’s just how he’s made! He has a good nose too, and helps me find badger setts when we’re out doing survey work with Lancashire Badger Group. To him, the word “badger” is just a scent. Jack is much more nimble than me and can cover steep-sided gullies and dense growth that’s difficult for me to search. He’s proved very useful.

Sadly, sett digging and badger baiting still goes on, so anything we can do to check that setts are safe is good. Jack doesn’t interfere with the setts – he just sniffs them out. I can usually tell by watching him whether a sett is active (occupied) or not. I met someone a few years ago who trained dogs for various purposes, and she’d trained a black Labrador to sniff out hedgehogs for its owner who carried out hedgehog surveys.

Jack recently had his 12th birthday and is still doing well. His grandmother, Tally, was adopted by Arlene when she was 8 years old and lived to the advanced dog age of 14. “He and Tally were polar opposites but both equally wonderful,” said Arlene. Before her Smooths, she had a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel for 14 years. There was also “Minnie Mouse,” and a “hand-tamed, wild, totally independent, very special blackbird” that flew to Arlene when she whistled for her. “Arlene is like Dr. Dolittle and has a way with animals,” Pat said. “I’d trust her with anything.”

“The world would be an awful place without animals. Without our dogs we’d not be the people we are now. They enrich our lives.” – Pat Howarth

If you’d like to get to know these lovely humans and learn or share more about Smooth Collies, I recommend joining the Smooth Talk Facebook community that Stephen, Finn, and Pat are part of. Pat said, “Both boys, Jack and Finn, are very much ‘people dogs’ – just wonderful, normal Smooths actually.”

Rolf: A New Beginning

Pat has now donated 2 puppies to search and rescue work. Finn fathered 2 litters with her dogs, and she kept Dream, one of his blue merle granddaughters. Rolf, a son of Dream, is nearly a year old now. Pat said, “I hope Rolf is half the dog Finn was,” and added that he is “also a brilliant pup.” She expects him to do well in his training, as “Steve knows just what he’s doing with them.”

Stephen said Rolf seems to be much the same as Finn, but perhaps with a bit more drive. “I think Rolf will be my last search dog,” he said. As long as nothing goes wrong with Rolf, Stephen plans to be a SARDA handler for another decade or so, which will put him into his late sixties. By then, he will have devoted nearly half a century to the business of search and rescue work. When I asked him if he will always have Collies, he wisely said, “What dog I have next will depend upon what fits the life I have in ten years’ time.”

“The partnership between dog and man is an ancient one, dogs being the first animals to be domesticated. I feel very privileged to have had the opportunity to train and work my search dogs. They have been my closest companions – spending more time in my company than family members and friends.”

Rescuers Need Resources

If you want to help Stephen, Rolf, and teammates continue their great work, consider making a donation. Remember, everything goes back into emergency training and equipment, not wages, and they truly are life-savers. Even a small amount can help cover the cost of fuel to transport the rescuers to locations where they are needed – so they don’t have to dip further into their own pockets.

If you can’t contribute financially, please share this story (or pages I linked to throughout) with others who possibly can, or to simply raise awareness. Follow this link if you are interested in becoming one of the CVRST “dogsbodies” who volunteer their time to help train the search dogs and see them in action. You can also click here to find out more about Mountain Rescue Search Dogs England. To keep up with Rolf’s progress specifically (as well as other dog/handler teams), visit Calder Valley Search and Rescue Team’s Facebook page.

Further Reading

- In Search of the Missing: Working with Search and Rescue Dogs by Mick McCarthy and Patricia Ahern

- Ten Thousand MIles with a Dog Sled: A Narrative of Winter Travel in Interior Alaska by Archdeacon Hudson Stuck

- Search dogs in the United States of America

- Search dogs in Canada

- Search dogs in Australia

*All pictures and quotes attributed to Stephen Garofalo unless otherwise indicated.